Southeast Asia Travel Narrative Story: A Tale of Two Cities

Story and photography by Ray Waddington.

Click/tap any image to scroll through a captioned slideshow and stock photography licensing terms.

I first visited northeastern Cambodia almost a quarter century ago. Back then, very few foreigners ventured to the area. Few Cambodians traveled there unless they had relatives in the area or they worked for the UN or for an NGO.

My first journey from Phnom Penh to Sen Monorom, the provincial capital of Mondulkiri, was arduous. The first leg took around six hours by boat upstream on the Mekong River. Three hours after disembarking, I had traveled only another forty kilometers. I was already questioning my sanity (as were my Cambodian travel companions) when I was sandwiched into the back of a pickup truck for the final, bumpy leg that would last another seven hours along an endless, waterlogged dirt road.

They say that sometimes the journey is the reward; not in this case. My sole reason for being there was to visit ethnic Mnong villages. Despite being classified as a town, Sen Monorom was really just a large village. Late the next morning (I needed the sleep), I walked to the official tourist office to inquire about a tour guide. They found one for me and then insisted that I sign the visitors' book — proudly informing me that I was officially their seventh tourist of the eleven-month-old year.

I walked around, took photos, ate lunch and returned to my guesthouse. There, I met a group of linguists who had been given the daunting task of learning and inventing an alphabet for the Mnong language. They were part of a broader indigenous literacy program recently undertaken by the Cambodian government. I didn't know it back then, but I would have an unexpected association with that program.

Early the next morning, I was a passenger on my guide's motorscooter as we set out for a five-day tour of the sweeping, forested Mondulkiri countryside.

After sleeping four nights in four Mnong villages, we returned. It was an immensely rewarding time. I learned a lot about that people's lifestyle, history and culture. I also had many fascinating experiences. Some of them are recounted in the above-linked photo-ethnographic essay.

Two hundred kilometers north of Sen Monorom lies Ban Lung. It is the provincial capital of Ratanakiri. Home to more of Cambodia's ethnic minority peoples, it is something of a sister town. I'd intended it to be my next destination. I knew the two towns were connected by a dirt road. After my journey to Sen Monorom, I felt I was up to the challenge. But the locals weren't. Even though it was the dry season, I could not find anyone willing to take me there.

Instead, I would have to brave a fifteen-hour return journey impersonating a sardine. Fortunately, back then, you could fly to Ban Lung. I was on the next flight.

About the same size as Sen Monorom, Ban Lung was an unappealing mix of constant atmospheric dust and little to do. I wasted no time finding a tour guide.

I spent a week in the area. During that time, I visited and stayed overnight in ethnic Kreung and Kavet villages. This was just as rewarding as my time in Mondulkiri.

Most of these villages were a long way from Ban Lung. They were all in areas devoid of any kind of infrastructure. I found myself beginning to understand the reluctance to bring me here by road from Sen Monorom: it could have been very dangerous. Still, I wondered what the impact would be to the small, indigenous communities along that road should it ever be developed.

My curiosity would be satisfied eventually. Less than a year after my time in Ratanakiri, that satisfaction was foreshadowed when I traveled the "Via Auca" to visit indigenous Huaorani communities in Ecuador.

I flew to Ban Lung again four years later. It had hardly changed. This time, I visited ethnic Kachok and Tampuan villages. Just like my last time here, the experience was as wonderful as any traveler might expect.

My most-unexpected experience came when my tour guide introduced me to a young man in a remote Tampuan village who spoke fluent Khmer and close-to-fluent English; he could also read those languages. That was surprising because I knew that his indigenous language had long been a pre-literate one and the two alphabets have nothing in common.

In further discussion, I learned that my "knowlege" was outdated. The same indigenous literacy program I mentioned above had completed inventing an alphabet for the Tampuan language. It turned out that the same young man could already read and write his own language as well.

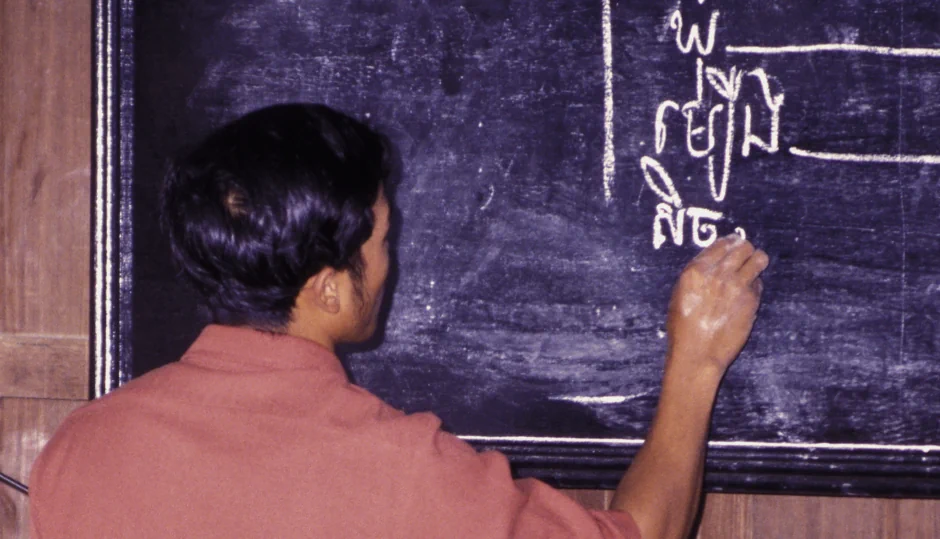

By sheer good fortune, there was a Tampuan literacy class being held in Ban Lung the next afternoon. After a bit of begging, I became one of the first outsiders allowed to observe it. Twenty years later, most Tampuan people can now read and write in their language if they have been to school.

The program has raised the overall education level of Cambodia's ethnic minority people by at least two orders of magnitude. I'd visited schools in the area when the program was still just a research project. Back then, attending school was largely a waste of time for the children.

I became even more fortunate when I was given permission to go inside the first Kreung school where the children were being taught the alphabet invented for their language. It was my first ever time in a Cambodian school where every student had pen-and-paper. As Malala Yousafzai said eight years later, "One child, one teacher, one pen and one book can change the world." She is correct.

The road down to Sen Monorom had not changed since my first visit. Although I had no plans to go there this time, I did ask out of curiosity about going there. Some told me it was possible. Almost everyone advised against it even though it was the dry season. I started to think that maybe the road held mythical properties in local folklore.

My next visit to the area came in 2012. Flights to Ban Lung were no longer a thing because the road there — as well as the road to Sen Monorom — had been paved. Even the main roads in both towns had been paved. The population had grown to the point that they now deserved to be called towns. More travelers were finding their way to these destinations. Most of the Khmer-style wooden buildings in both towns had been replaced by concrete ones. Alas, the connecting road had still not been paved and it was the beginning of the rainy season anyway. I now wondered whether I would ever get to travel that road.

Late last year, I returned to the area for what will likely be the last time. I started in Ban Lung. Compared with my first visit all those years ago, it was unrecognizable. Almost every road and street is now paved. There are no more wooden buildings. Some of the newer buildings are up to a dozen stories high. There is even a supermarket.

None of this might seem like a big deal to Western readers. But the arterial roads to the surrounding indigenous villages are also now being paved. This development makes it much easier for the villagers to trade (they no longer have to spend hours walking to Ban Lung), which grows their economy and their wealth. It also makes it easier for indigenous children to attend school if their village has no school of its own. It also opens up higher education access since such facilities exist only in Ban Lung.

A few years ago, the road down to Sen Monorom became the final main dirt road to be paved in Cambodia thanks to a loan from China. There are frequent bus and minivan services, and I finally got to travel the three hours it now takes.

Sen Monorom had changed in all the same ways as Ban Lung. It is still considered a sister town. Unlike my first experience traveling there, this time the journey was the reward.

Although I had no prior experience to compare it to, I had some idea of what to expect traveling this road. I'd already read about the extensive deforestation in the area. It was clear that the paving of the road had accelerated the rate of deforestation. In place of the previous forest was mainly industrial-scale agribusiness.

There are still some of the small, indigenous farming villages that characterized the area before the road was paved. The inhabitants no longer live in wooden-hut houses, and they now live among an ever-growing population of ethnic Khmer who exploit them financially.

This was most evident in what is now a small town about half way — Kaoh Nheak just on the Mondulkiri side of the provincial border. For all its modernization, I saw something I likely would have seen there when I first visited the area: a pig was hitching a ride with human travelers.

It's rare to see any part of the world go through hundreds of years of progress in just one generation even if you live there. Yet the same kinds of changes I've seen in these two towns (they'll soon be big enough to be called cities) are happening all the time in the developing world even if on a longer timeline. I am priveleged to witness it and write about it.

Photography copyright © 1999 -

2026,

Ray Waddington. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 1999 -

2026,

The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R., (2025) A Tale of Two Cities. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved

February 16, 2026,

from The Peoples of the World Foundation.

<https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/travelStory.jsp?travelStory=tale%20of%20two%20cities>

If you enjoyed reading this travel story, please consider buying us a coffee to help us cover the cost of hosting our web site. Please click on the link or scan the QR code. Thanks!