The Indigenous Tampuan People

Ethnonyms: Campuon, Kha Tampuon, Proon, Proons, Tamphuan, Tampuen, Tampuon Countries inhabited: Cambodia Language family: Austroasiatic Language branch: Mon-Khmer

The photographs on this page are copyright by Thomas Weber Carlsen. They are from from his 2002 documentary film, Anger of the Spirits. He is on our Board of Advisors. He is an ethnographic documentary film maker from Denmark. The text is mainly adapted from the same film, supplemented by observations made during my own time spent with the Tampuan.

The Tampuan live in the northeastern province of Cambodia, Ratanakiri. Combined with the

six other indigenous groups who live there, they form the majority of the ethnic make up of the population.

Many Tampuan live in villages close

to Ratanakiri's provincial capital, Ban Lung, in an area around a large volcanic crater lake, Yeak

Laom, formed thousands of years ago. Others live in scattered communities in the

province, many of which are to be found around the small town of Voeun Sai.

The Tampuan live in the northeastern province of Cambodia, Ratanakiri. Combined with the

six other indigenous groups who live there, they form the majority of the ethnic make up of the population.

Many Tampuan live in villages close

to Ratanakiri's provincial capital, Ban Lung, in an area around a large volcanic crater lake, Yeak

Laom, formed thousands of years ago. Others live in scattered communities in the

province, many of which are to be found around the small town of Voeun Sai.

But wherever they live, the Tampuan are today on the border of irreversible

lifestyle and cultural changes. On the old side of this border Tampuan tradition is

dominated by traditional belief: spirits live among them; illness is cured

by herbal medicines and animal sacrifice; Tampuan mythology and folklore define

their identity; money does not exist —

barter is the only currency through which

to conduct the trading of goods.

barter is the only currency through which

to conduct the trading of goods.

On the new side are a transition from Animism

to Buddhism and Christianity and the use of Western medicines.

On the new side are a transition from Animism

to Buddhism and Christianity and the use of Western medicines.

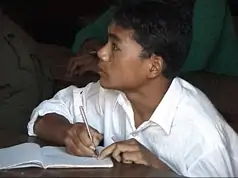

Pictured left are a group of Tampuan in traditional dress performing traditional Tampuan dances. Although the scene appears to be a part of the tradition that lies on the old side of the border, it was actually filmed in a wider context. A Cambodian television production crew had come to the area from Phnom Penh to film a staged-for-television event. Pictured above right is a young Tampuan boy, Pon Duin, who is part of the first generation of Tampuan ever to attend school. Indigenous peoples today account for only 10% of students at Ban Lung's high school. This is partly because many older generation Tampuan did not go to school themselves and don't fully understand the value of formal education, or they are simply too poor to send their children to school.

A further reason is that they are not taught in their own language and so they must study extra hard to learn the

national Khmer language in order to understand the lessons. But this extra work may soon not be required.

Linguists have been working with the Tampuan to develop an alphabet for

their native Tampuan language — which has never been written before. It took

five years to perfect the new alphabet! The

possibility of becoming literate in their first language, and eventually being

schooled using written materials in that language, should increase the incidence

of education among the Tampuan in the coming generations.

A further reason is that they are not taught in their own language and so they must study extra hard to learn the

national Khmer language in order to understand the lessons. But this extra work may soon not be required.

Linguists have been working with the Tampuan to develop an alphabet for

their native Tampuan language — which has never been written before. It took

five years to perfect the new alphabet! The

possibility of becoming literate in their first language, and eventually being

schooled using written materials in that language, should increase the incidence

of education among the Tampuan in the coming generations.

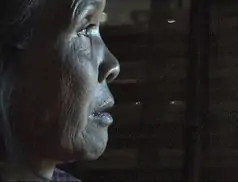

While barter is still the currency in Tampuan villages, some money comes from

selling food at the Ban Lung market. The old woman pictured above left, Lon Dom,

sold whatever she was able to carry in her basket for the four kilometer (2.5

miles) walk to

the market. That day she made 700 Cambodian riel (about 15 US cents).

Selling food will not send the next generation of Tampuan children to school!

Selling food will not send the next generation of Tampuan children to school!

Lon Dom (pictured again, left) has a special place in her village. She is a spirit medium. "All spirits are strong if we respect them and sacrifice to them," she explains during one scene. Lon Dom is also the narrator of an ancient Tampuan fable. In this story a huntsman named Sglo shoots a crocodile with his crossbow at Yeak Laom. The crocodile then sinks to the bottom of the lake. The spirits of the lake then come to his house for his wife, knowing she is a spirit medium who can heal the crocodile. Upon healing it, she discovers the arrow and saves it. The spirits pay her with rice, money and meat. On her way home the rice turns into sand, the money into leaves and the meat into wood. When she gets home and matches the arrow with one of her husband's she gets very angry with him.

In telling this story, as well as in her interviews, Lon Dom is lamenting the changes she has seen in Tampuan life.

She makes many comments about past customs that today's generation no longer observes. The crocodile story is

perhaps her way of reminding us of its warning — that the spirits should not be angered. Although many of these

stories from Tampuan folklore have been lost, the introduction of native language literacy will be a huge step

toward preserving the ones that are still remembered.

In telling this story, as well as in her interviews, Lon Dom is lamenting the changes she has seen in Tampuan life.

She makes many comments about past customs that today's generation no longer observes. The crocodile story is

perhaps her way of reminding us of its warning — that the spirits should not be angered. Although many of these

stories from Tampuan folklore have been lost, the introduction of native language literacy will be a huge step

toward preserving the ones that are still remembered.

As a spirit medium Lon Dom uses many tools. One of these is her spirit drum. In this scene, the drum skin is being

replaced by a new one. It may sound mundane, but a night-long village ceremony is held, lasting from sunset to

sunrise, for the new drum skin's inauguration! Both a cock and a hen are sacrificed to summon the spirits of the

drum.

After dancing and praying to these spirits Lon Dom enters into a trance and is possessed by them and they

speak through her.

After dancing and praying to these spirits Lon Dom enters into a trance and is possessed by them and they

speak through her.

We see her connection to the spirits in a further scene involving healing. The woman on the left had contracted malaria. Her family buys a water buffalo and sacrifices it to the spirits in the belief that this will appease them and they will decide to spare her life. As one man explains, if they took her to the hospital instead, the spirit possessing her might still be inside her when she came home. Despite the feast ("when we sacrifice an animal and eat it, the spirits come to feast with us," explains Lon Dom), the woman is not cured by the sacrifice and Lon Dom is asked to perform an exorcism.

Lon Dom agrees to perform the ritual.

Small spirit houses are made to lure the spirits out of the suffering woman's body. A pig and a cock are sacrificed

to make the spirits happy. Tinder is placed around the patient's body and burned to drive the spirits out of her. The

next morning she is feeling better. Six months later she is completely cured. Of course, science has no explanation for this,

and it should be noted that the woman was occasionally given malaria pills during those six months. Her husband later

explained that the sacrifices and the exorcism were the main reason for the cure. The Tampuan do not view the malaria

pills as an alternate explanation. Rather, they see both forms of healing as the same kind of magic.

Small spirit houses are made to lure the spirits out of the suffering woman's body. A pig and a cock are sacrificed

to make the spirits happy. Tinder is placed around the patient's body and burned to drive the spirits out of her. The

next morning she is feeling better. Six months later she is completely cured. Of course, science has no explanation for this,

and it should be noted that the woman was occasionally given malaria pills during those six months. Her husband later

explained that the sacrifices and the exorcism were the main reason for the cure. The Tampuan do not view the malaria

pills as an alternate explanation. Rather, they see both forms of healing as the same kind of magic.

After Lon Dom dies there will be few, if any, Tampuan left like her. Spiritually-based customs such as animal

sacrifice will still continue, but with her will pass a significant chapter in their history.

They will be another step closer to finally crossing the border from old to new.

On the new side will be people like Leang Venai, pictured left. Along with Pon Duin, the young schoolboy pictured

earlier, he understands the importance of education. Both young boys go to school and are already learning Khmer

and even some English. Both reject the stereotype held about them in mainstream Cambodian society, which is that

they cannot learn and are good only for farming. Both are proving the stereotype to be wrong. And both want to

use their education to help their fellow Tampuan by returning to their villages and teaching what they have learned.

They will be another step closer to finally crossing the border from old to new.

On the new side will be people like Leang Venai, pictured left. Along with Pon Duin, the young schoolboy pictured

earlier, he understands the importance of education. Both young boys go to school and are already learning Khmer

and even some English. Both reject the stereotype held about them in mainstream Cambodian society, which is that

they cannot learn and are good only for farming. Both are proving the stereotype to be wrong. And both want to

use their education to help their fellow Tampuan by returning to their villages and teaching what they have learned.

Like all pioneers, though, theirs is a struggle. Their schooling is often interrupted by lack of money. In Pon Duin's case, it was the sickness of his mother — who eventually dies in Weber Carlsen's documentary — that interrupted his studies. Leang Venai faces conflict with his father (pictured right), despite his father's wish for a better future for him. While both see that education is the best way to a better future, they seem to disagree on how that education should be provided. Cambodia is among the World's poorest countries. Ratanakiri is one of its poorest provinces. It is ironic to consider that those Tampuan who value education aspire to the quality of life experienced by their Khmer neighbors. Yet they also see the value of education in its ability to help them maintain their culture and bring it with them across the border of modernization.

Photography copyright © 2002, Thomas Weber Carlsen. All rights reserved. Text copyright © 1999 - 2026, The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R. (2003), The Indigenous Tampuan People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved March 3, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Tampuan>