Indigenous Calendar January, 2014: A Quichua Oratorio

There is something intriguing about Andean culture. By their very nature, high-altitude, mountainous terrains make for a way of life that is alien to most of us who've never lived in such a region. Geographic mobility is limited and communities tend to be smaller and more closely knit than elsewhere. This is perhaps the reason why traditions have endured here at least to an extent comparable with any other region in the world.

My first experience of the High Andes was in Ecuador. As I often do when on assignment, I abandoned my guidebook and prior research and instead sought out local opinion on where best to spend my time. A consensus emerged about a few small Quichua communities that were, essentially, in the middle of nowhere. Transportation to and among these communities was unreliable, I was told. Nor was Spanish widely spoken (I don't speak any Quechua) and facilities were basic to non-existent. I generally enjoy getting off the beaten path but the next ten days or so (as planned — but it could easily have taken longer to complete the circuit I'd intended to follow) would be a challenge.

As the bus pulled away from my Ecuadorian base — Latacunga — early one morning I truly wondered whether I was tempting fate this time. I was the only gringo on the almost-full bus and I was the object of some very disbelieving stares. By late afternoon the bus had somewhat arrived at my first destination; I was instructed to get out of the bus when it stopped on the main road about a kilometer from a small settlement. It looked much smaller than the place I was expecting based on my research in Latacunga. I was the only passenger getting off the bus and there was nobody around to ask for directions on how to get to the settlement or whether it was indeed the one I'd intended to come to!

Eventually I found the path from the road to the village. I didn't meet anyone else on it and there were few people around in the village once I arrived there. Fortunately one of those few people spoke enough Spanish to direct me to a small hostel. With a roof over my head guaranteed for the night I checked in without even looking at the room — breaking what is almost a golden rule for me.

I freshened up and began exploring. There were still very few people outside in the early evening as I made my way to what appeared to be the village square. There were more people in the square itself and I got the impression that preparations were being made for some event. My Spanish is conversational not fluent. Coupled with only basic Spanish being spoken in the village the only confirmable information I could gather was that some kind of festival was scheduled for the next day and that it began "very early." I took the opportunity to find out where I could eat dinner and was advised of a "place" that could accommodate me as long as I arrived no later than 6:30.

Since it was already around 6 o'clock I went straight there; I was the only customer. The owners were very pleasant and took an interest in me — the food was quite good too. I learned that the festival was an annual tradition in the village and involved various activities such as singing and playing games. When I left the "place" (restaurant would be the wrong word) it was dark and there was nobody out on the streets, even though it was only about 7 o'clock. Fortunately the hostel was not far away. My only fear was whether I might be locked out having returned too late! I think I was the only guest that night. The place was still open but not a soul was in sight. I went to my room and watched TV wondering what the next day had in store.

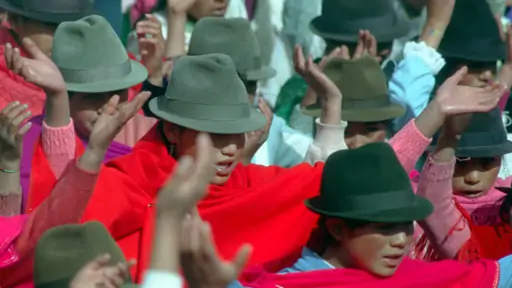

"Very early" the next morning villagers were seen swarming in the direction of the village square. Women especially were dressed very finely. My camera and I followed them and were treated to a splendid oratorio. It was rendered entirely in Spanish that was being read from written lyrics. I never did find out why the songs were no longer sung in the indigenous Quechua language.

If you enjoyed reading this article, please consider supporting independent, advertising-free journalism by buying us a coffee to help us cover the cost of hosting our web site. Please click on the link or scan the QR code. Thanks!