Southeast Asia Travel Narrative Story: Today's Khmer Rouge

Story and photography by Ray Waddington.

The Khmer Rouge are probably best known because of the term "The Killing

Fields," which is the title of Roland Joffé's 1984 film about an American

journalist and his Cambodian assistant caught up in Khmer Rouge Cambodia. In the

four years between 1975 and 1979 the Khmer Rouge murdered around two million people — about

a third of Cambodia's population. (The "official" Cambodian number is 3.1

million.) It is said that every Cambodian family lost at least one member to the

Khmer Rouge.

The Khmer Rouge are probably best known because of the term "The Killing

Fields," which is the title of Roland Joffé's 1984 film about an American

journalist and his Cambodian assistant caught up in Khmer Rouge Cambodia. In the

four years between 1975 and 1979 the Khmer Rouge murdered around two million people — about

a third of Cambodia's population. (The "official" Cambodian number is 3.1

million.) It is said that every Cambodian family lost at least one member to the

Khmer Rouge.

This ultra-communist regime, led by the infamous Pol Pot, were

anti-just-about-everything. Schools were outlawed and their teachers killed.

People from all walks of life were tortured and/or killed for no reason, or

because of the slightest suspicion that they might not adhere to Pot's vision.

People were forced to choose between their own life and executing another family

member. Those not killed were forced into hard labor in an

attempt to establish a moneyless, egalitarian, totally agrarian society.

because of the slightest suspicion that they might not adhere to Pot's vision.

People were forced to choose between their own life and executing another family

member. Those not killed were forced into hard labor in an

attempt to establish a moneyless, egalitarian, totally agrarian society.

At the end of 1978 Vietnamese forces invaded Cambodia and, within weeks,

militarily defeated the Khmer Rouge regime, although they would end up occupying

Cambodia for the next decade.

At that time the core Khmer Rouge leaders and

fighters retreated to southwestern Cambodia. It was here that they would mount a

resistance that was to last another 20 years. One of the last Khmer Rouge

strongholds to fall to the Cambodian army was the town of Pailin, in March,

At that time the core Khmer Rouge leaders and

fighters retreated to southwestern Cambodia. It was here that they would mount a

resistance that was to last another 20 years. One of the last Khmer Rouge

strongholds to fall to the Cambodian army was the town of Pailin, in March,

1994, with the majority of the remaining fighters surrendering in 1996. It was

in and around Pailin that these pictures were taken and former Khmer Rouge

guerillas interviewed.

1994, with the majority of the remaining fighters surrendering in 1996. It was

in and around Pailin that these pictures were taken and former Khmer Rouge

guerillas interviewed.

Pailin is considered a somewhat dangerous

town to this day. Lawlessness abounds and takes on many forms including illegal

logging, prostitution and the clandestine export of precious gemstones — mainly rubies and

sapphires.

While a fortunate few get very rich from mining gemstones, labor

conditions are harsh and child labor is common. The two children pictured left

work almost every daylight hour, seven days a week. They are mainly employed to

sift small gemstones from the dirt that is brought out of the mines.

They are used in this role because of both

their better eyesight and their lack of rights in asking for payment.

Pailin is considered a somewhat dangerous

town to this day. Lawlessness abounds and takes on many forms including illegal

logging, prostitution and the clandestine export of precious gemstones — mainly rubies and

sapphires.

While a fortunate few get very rich from mining gemstones, labor

conditions are harsh and child labor is common. The two children pictured left

work almost every daylight hour, seven days a week. They are mainly employed to

sift small gemstones from the dirt that is brought out of the mines.

They are used in this role because of both

their better eyesight and their lack of rights in asking for payment.

In return for their labor they are allowed to keep the smallest, largely worthless stones.

It was mainly the gemstone and logging industries that funded the Khmer Rouge's

resistance in this area.

In return for their labor they are allowed to keep the smallest, largely worthless stones.

It was mainly the gemstone and logging industries that funded the Khmer Rouge's

resistance in this area.

A far cry from their one time ideology, many of these industries are operated in Pailin by former Khmer Rouge leaders and their families. That they are allowed to live in freedom, political and economic empowerment and relative luxury, is their amnesty for agreeing to surrender and defect to Prime Minister Hun Sen's government and cease their fighting.

Sala Krat is a small, rural village outside

Pailin. It is inhabited almost entirely by the last Khmer Rouge to surrender and

their families. The scars of war are still very apparent in this village,

Sala Krat is a small, rural village outside

Pailin. It is inhabited almost entirely by the last Khmer Rouge to surrender and

their families. The scars of war are still very apparent in this village,

even though it is a very quiet place these days. This part of Cambodia remains one of

the most heavily landmined places in the world and explosions are still quite frequent.

even though it is a very quiet place these days. This part of Cambodia remains one of

the most heavily landmined places in the world and explosions are still quite frequent.

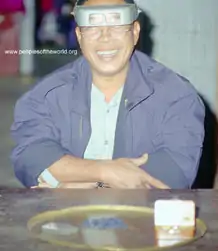

Tan, 36, pictured right, fought in Pailin right up until 1996. He now works as a carpenter and is married with four children. He is fortunate enough to have lost no limbs, unlike the man pictured below left, who lost all but his left arm. Choup, pictured below right with his daughter, is 30 years old. He joined the Khmer Rouge when he was just sixteen. In 1993 he lost his right leg while fighting against government forces in Pailin. Today he runs a small farm with his wife. He told me that one day he intends to tell his daughter everything about his past in an attempt to pass on to her an anti-war attitude.

The atrocities committed by the Khmer Rouge have largely gone unpunished.

Cambodia today is one of the poorest countries in the world

and if it ever recovers from the events of 1975-1979, it will surely be many generations before

anyone can realistically apply the word "recover." In 2001 the United Nations

negotiated terms with the Cambodian government to establish trial procedures for

the remaining Khmer Rouge leaders.

(Pol Pot himself is said to have died in 1998.) Only one of them, Kang Kek Iew, has undergone

such a trial and been convicted.

Cambodia today is one of the poorest countries in the world

and if it ever recovers from the events of 1975-1979, it will surely be many generations before

anyone can realistically apply the word "recover." In 2001 the United Nations

negotiated terms with the Cambodian government to establish trial procedures for

the remaining Khmer Rouge leaders.

(Pol Pot himself is said to have died in 1998.) Only one of them, Kang Kek Iew, has undergone

such a trial and been convicted.

Many observers have not been surprised by

the lack of justice. Cambodia is well known for corruption at all levels of

government and for failing to enforce its own legal system. When Hun Sen —

himself a former Khmer Rouge commander — was "voted" Prime Minister for the

third time in July, 2003, the prospect of Khmer Rouge trials took another step

backwards.

At the same time, Pol Pot's (first) wife, Khieu Ponnary, died. Had

the trials already commenced, she might have been a key witness.

At the same time, Pol Pot's (first) wife, Khieu Ponnary, died. Had

the trials already commenced, she might have been a key witness.

While most want to see justice done before the ageing defendants die, many

also fear that to go ahead with the proposed trials will bring further fighting

and instability to a country already in a delicate balance. Many of my questions

in Sala Krat were met with blank or contradictory answers. For example, some

said they had burned their Khmer Rouge military uniforms while others said their

uniforms were hidden so deep in the forest that it was impractical to take me to

see them. Road blocks, like the one pictured right,

were quite common after leaving Pailin;

While most want to see justice done before the ageing defendants die, many

also fear that to go ahead with the proposed trials will bring further fighting

and instability to a country already in a delicate balance. Many of my questions

in Sala Krat were met with blank or contradictory answers. For example, some

said they had burned their Khmer Rouge military uniforms while others said their

uniforms were hidden so deep in the forest that it was impractical to take me to

see them. Road blocks, like the one pictured right,

were quite common after leaving Pailin;

locals were allowed to pass but whatever

lay beyond was strictly off limits to foreigners.

Many Cambodians are reported to believe that

weapons caches might still lay hidden in these forests,

being saved for a final

wave of fighting by some should their former leaders be brought to trial.

locals were allowed to pass but whatever

lay beyond was strictly off limits to foreigners.

Many Cambodians are reported to believe that

weapons caches might still lay hidden in these forests,

being saved for a final

wave of fighting by some should their former leaders be brought to trial.

It can appear that life is back to normal in and around Pailin. Indeed, for many it is. At a traditional Khmer wedding in Sala Krat the couple and the guests might even feel they are in an era that long pre-dates the Khmer Rouge. Or perhaps they are simply comfortable in the knowledge that their future is no more or less predictable than that of others in the country. They may be divided only by their ambivalence to see some form of justice done. Even if that justice is more symbolic than real, it just might have a mass psychological impact on a people who will soon commemorate the 40th. anniversary of the Khmer Rouge takeover of the capital, Phnom Penh.

Photography copyright © 1999 -

2026,

Ray Waddington. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 1999 -

2026,

The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R., (2004) Today's Khmer Rouge. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved

February 16, 2026,

from The Peoples of the World Foundation.

<https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/travelStory.jsp?travelStory=khmer%20rouge>

Web Links

Cambodian Genocide Program

Khmer Rouge Tribunal on Wikipedia

Documentation Center of Cambodia

Books

Y. Ly and J.S. Driscoll (Eds.), (2000) Heaven Becomes Hell: A Survivor's Story of Life Under the Khmer Rouge. New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies Monograph Series, No 50.

B. Kiernan (Ed.), (1993) Genocide and Democracy in Cambodia: The Khmer Rouge, the U.N., and the International Community. New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies Monograph Series, No 41.

If you enjoyed reading this travel story, please consider buying us a coffee to help us cover the cost of hosting our web site. Please click on the link or scan the QR code. Thanks!