South America Travel Narrative Story: On Being Indigenous

Story and photography by Ray Waddington.

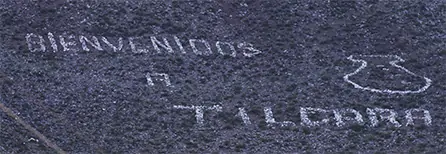

Andean mountains surround the small, northern Argentinean town of San Francisco de Tilcara. Stones have been placed strategically atop one of those mountains

to spell out a welcome in large letters to attract visitors who see them from far away.

Andean mountains surround the small, northern Argentinean town of San Francisco de Tilcara. Stones have been placed strategically atop one of those mountains

to spell out a welcome in large letters to attract visitors who see them from far away.

Painted on stone, colonial buildings in the town center is the declaration that Tilcara is, officially, an indigenous community.

Painted on stone, colonial buildings in the town center is the declaration that Tilcara is, officially, an indigenous community.

But what does that mean?

The archaeological record from the region is clear: it was populated at least ten thousand years ago by humans. They should be recognized as the area's

original, indigenous inhabitants. They built many settlements in the region: but the one pictured on the right is not one of them. It is, instead, the

partial reconstruction of one — a pre-Inca fortress that was built on the same land and known as the Pucará de Tilcara.

The archaeological record from the region is clear: it was populated at least ten thousand years ago by humans. They should be recognized as the area's

original, indigenous inhabitants. They built many settlements in the region: but the one pictured on the right is not one of them. It is, instead, the

partial reconstruction of one — a pre-Inca fortress that was built on the same land and known as the Pucará de Tilcara.

The fortress was almost certainly built originally by the Omaguaca people — who were among the direct descendants of Argentina's original,

indigenous inhabitants.

The fortress was almost certainly built originally by the Omaguaca people — who were among the direct descendants of Argentina's original,

indigenous inhabitants.

When the Pucará de Tilcara fortress was rediscovered by archaeologists, it was a collection of scattered stones on the ground, much like those pictured on the left at an un-reconstructed part of the site. It has greater significance to archaeologists, historians and anthropologists in that un-reconstructed form. But it attracts more tourists in its reconstructed form.

Tilcara is the geographically central of the three main towns of the Quebrada de Humahuaca valley — named after the town of Humahuaca to the north

— in the Argentinean province of Jujuy.

The tiny town of Purmamarca lies to the south. While the whole area has many pre-historic sites such as the Tilcara fortress, the other two towns do not,

officially at least, proclaim themselves to be indigenous communities. Tilcara has capitalized the most on the Quebrada de Humahuaca becoming a World

Heritage site.

Tilcara is the geographically central of the three main towns of the Quebrada de Humahuaca valley — named after the town of Humahuaca to the north

— in the Argentinean province of Jujuy.

The tiny town of Purmamarca lies to the south. While the whole area has many pre-historic sites such as the Tilcara fortress, the other two towns do not,

officially at least, proclaim themselves to be indigenous communities. Tilcara has capitalized the most on the Quebrada de Humahuaca becoming a World

Heritage site.

I shot a few videos in the town of Humahuaca. They are available on our YouTube channel at the link at the bottom of this page.

The performers display the indigenous musical heritage of the area very clearly: guitar-like instruments, drums and pan flutes

are known to pre-date both the Spanish and the Inca in the area. But does this make these men indigenous people?

The performers display the indigenous musical heritage of the area very clearly: guitar-like instruments, drums and pan flutes

are known to pre-date both the Spanish and the Inca in the area. But does this make these men indigenous people?

Early one evening in Tilcara I came across a band of musicians performing while parading through the streets, many of whom were playing pan flutes. When I asked them why they were doing this they told me it was to keep indigenous traditions alive in their community.

Earlier in the day I had visited the museum of archaeology in Tilcara. While the museum features mainly artifacts from the pre-history of the region, it also has information about the town's gaucho (cowboy) festival. Horses are not indigenous to the region, so it is scientifically incorrect to include references to Argentina's gaucho culture in the museum. But it attracts more tourists by doing so.

Llamas and alpacas are both indigenous to the region. They were originally domesticated by indigenous humans to provide wool

for clothing and to be eaten. They fill the same roles today, but for tourists also. Some clothes are still handmade using the wool, but those

on offer in the town's marketplaces are almost all mass produced these days.

Llamas and alpacas are both indigenous to the region. They were originally domesticated by indigenous humans to provide wool

for clothing and to be eaten. They fill the same roles today, but for tourists also. Some clothes are still handmade using the wool, but those

on offer in the town's marketplaces are almost all mass produced these days.

Perhaps the main reason people visit the area is for the scenery, which is so spectacular that no guidebook could do it justice — although most of them try to. Many of them also make the mistake of comparing the towns in the region on a scale of "indigenousness."

It is impossible to know after so many years of Inca and Spanish colonization what the region's true population of indigenous descent is. Argentina's

official population of indigenous descent is underreported in any case due to the often-perceived need to hide their origin because of

discrimination against them. The whole question of indigenous identity is, these days, influenced by a complex interplay of history, cultural

survival and a willingness even to acknowledge one's past.

It is impossible to know after so many years of Inca and Spanish colonization what the region's true population of indigenous descent is. Argentina's

official population of indigenous descent is underreported in any case due to the often-perceived need to hide their origin because of

discrimination against them. The whole question of indigenous identity is, these days, influenced by a complex interplay of history, cultural

survival and a willingness even to acknowledge one's past.

Traditional and Modern Indigenous Andean Music (short film on YouTube).

Photography and videography copyright © 1999 -

2026,

Ray Waddington. All rights reserved.

Text copyright © 1999 -

2026,

The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R., (2016) On Being Indigenous. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved

February 16, 2026,

from The Peoples of the World Foundation.

<https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/travelStory.jsp?travelStory=indigenous>

If you enjoyed reading this travel story, please consider buying us a coffee to help us cover the cost of hosting our web site. Please click on the link or scan the QR code. Thanks!