The Indigenous Palaung People

Ethnonyms: Bulai, Dlang, Palay, Pale, Palong, Pulei, Shwe, Ta'ang Countries inhabited: Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, China Language family: Austroasiatic Language branch: Mon-Khmer

The Palaung are the most recent ethnic group to arrive in Thailand. They have come here

from neighboring Burma (Myanmar), where they are one of that country's most ancient indigenous peoples. They have fled

in the past 20 years from Shan State and Kachin State

to escape persecution and oppression at the hands of Burma's military rulers. Many of the

Palaung in Thailand are refugees living in refugee camps.

The Palaung are the most recent ethnic group to arrive in Thailand. They have come here

from neighboring Burma (Myanmar), where they are one of that country's most ancient indigenous peoples. They have fled

in the past 20 years from Shan State and Kachin State

to escape persecution and oppression at the hands of Burma's military rulers. Many of the

Palaung in Thailand are refugees living in refugee camps.

The are three main sub-groups of the Palaung: Pale, Shwe and Rumai. Each of these sub-groups

has their own language. Most of the Palaung who settled in northern Thailand are of the Pale, also known

as Silver Palaung. The photographs here are of this sub-group.

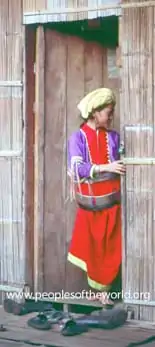

Their women are very distinct in their dress. This includes a bright red skirt, worn like a sarong. Typically in the

past these "tube skirts" were made from cotton, which the Pale grew and dyed themselves, and were hand woven.

Nowadays, the cloth is more commonly bought in markets and hand weaving is giving way to machines.

Around their waist are worn quite heavy silver hoops. These are said to symbolize an animal trap, set by the

Lisu people, which accidentally ensnared Roi Ngoen, a visiting angel

from whom they believe they are descended.

The hoops are also believed to afford protection to the women.

Around their waist are worn quite heavy silver hoops. These are said to symbolize an animal trap, set by the

Lisu people, which accidentally ensnared Roi Ngoen, a visiting angel

from whom they believe they are descended.

The hoops are also believed to afford protection to the women.

The Palaung traditionally have practiced a mixture of Animism and Buddhism. (Although there has been a

small amount of recent Christian missionary work among them.)

Whereas many associate Buddhism with a pacifistic lifestyle,

the Palaung in Burma have a 40-year history of armed resistance through the Palaung State Liberation

Army — the military wing of their political liberation organization. Even though a cease-fire has been

in effect for the past 12 years, the Palaung State Liberation Front has been associated with other

ethnic minority-led armed resistance movements in Burma. They are currently trying to secure three-way peace talks

between Burma's military rulers, the pan-ethnic armed resistance movements and the

national pro-democracy leader, Aung San Suu Kyi.

The Palaung traditionally have practiced a mixture of Animism and Buddhism. (Although there has been a

small amount of recent Christian missionary work among them.)

Whereas many associate Buddhism with a pacifistic lifestyle,

the Palaung in Burma have a 40-year history of armed resistance through the Palaung State Liberation

Army — the military wing of their political liberation organization. Even though a cease-fire has been

in effect for the past 12 years, the Palaung State Liberation Front has been associated with other

ethnic minority-led armed resistance movements in Burma. They are currently trying to secure three-way peace talks

between Burma's military rulers, the pan-ethnic armed resistance movements and the

national pro-democracy leader, Aung San Suu Kyi.

Like many others in Burma and Thailand who are nominally Buddhist, the Palaung also still

practice various forms of Animist ritual from their religious past.

The most famous such ritual is known as "nat worship." Nats are believed to be the spirits of otherwise

inanimate objects such as rocks, mountains and rivers, as well as the spirits of deceased

ancestors. There are traditionally 37 different nats, to whom offerings of, for example, betel and tobacco are

made on various ceremonial occasions — or simply to appease these spirits if someone falls sick or if a crop

harvest has been bad.

"Nat wives" are women who have "married" such a spirit, and are sometimes transvestite and/or homosexual

men (see the Nat worship documentary link below). Offerings to nats and other Animist rituals are performed at events such as weddings, births

and funerals by Palaung shamans, who are both respected and powerful in their communities.

Like many others in Burma and Thailand who are nominally Buddhist, the Palaung also still

practice various forms of Animist ritual from their religious past.

The most famous such ritual is known as "nat worship." Nats are believed to be the spirits of otherwise

inanimate objects such as rocks, mountains and rivers, as well as the spirits of deceased

ancestors. There are traditionally 37 different nats, to whom offerings of, for example, betel and tobacco are

made on various ceremonial occasions — or simply to appease these spirits if someone falls sick or if a crop

harvest has been bad.

"Nat wives" are women who have "married" such a spirit, and are sometimes transvestite and/or homosexual

men (see the Nat worship documentary link below). Offerings to nats and other Animist rituals are performed at events such as weddings, births

and funerals by Palaung shamans, who are both respected and powerful in their communities.

In 19th Century Burma, under British colonial rule, the Palaung were far more powerful in terms of land ownership

and political representation than they are today.

The British even recognized the Palaung-controlled kingdom of

Tawnpeng. Today land ownership is being taken away from the Palaung by Burma's military government. In Thailand

many Palaung work as hired laborers on Thai-owned farms.

To the extent that they continue to own land, they farm

a variety of crops including tea, grain, rice, opium poppy, betel and corn.

In 19th Century Burma, under British colonial rule, the Palaung were far more powerful in terms of land ownership

and political representation than they are today.

The British even recognized the Palaung-controlled kingdom of

Tawnpeng. Today land ownership is being taken away from the Palaung by Burma's military government. In Thailand

many Palaung work as hired laborers on Thai-owned farms.

To the extent that they continue to own land, they farm

a variety of crops including tea, grain, rice, opium poppy, betel and corn.

The photographs left and right show the Palaung harvesting corn and carrying it back to their village. While corn

is a recent addition to the crops of the Palaung, others such as rice, tea and opium poppy are generations old.

Historically, and extending to the present day, opium poppy has been a lucrative cash crop to the Palaung. In

Thailand, government control and the efforts of non-governmental organizations have, for the most part, persuaded

them to cultivate alternate cash crops such as coffee and beans. Efforts along these same lines in Burma lag behind

those in Thailand, but are now underway.

Nonetheless, peoples like the Palaung live in poverty relative to their immediate neighbors,

Nonetheless, peoples like the Palaung live in poverty relative to their immediate neighbors,

and, due to the power of local druglords, as well as the corruption of law enforcers, it will

be a long time, if ever, before they abandon opium poppy cultivation.

(The visitor to

the border areas of northern Thailand can expect to be spot-searched for drugs by Thai authorities.)

and, due to the power of local druglords, as well as the corruption of law enforcers, it will

be a long time, if ever, before they abandon opium poppy cultivation.

(The visitor to

the border areas of northern Thailand can expect to be spot-searched for drugs by Thai authorities.)

Besides alternate cash crops, the Palaung have recently begun selling handicrafts to tourists to supplement

their income. This is especially prevalent in northern Thailand, where many tour operators and guides take

trekkers into Palaung villages. This type of tourism takes place to a lesser degree in Burma also. They

sell, among other things, shoulder bags, wallets, hand-woven cloth and hand-made clothes. The visitor can stay overnight

in some of these villages,

which have basic yet comfortable wooden guest huts that have been purpose-built to accommodate tourists.

which have basic yet comfortable wooden guest huts that have been purpose-built to accommodate tourists.

The visitor might be surprised by how well these guest huts are built. The Palaung are highly skilled in

construction. Their own houses are also wooden huts, which are raised high off the ground on stilts. These

days their houses are typically much smaller than in the past. Traditionally their houses have been longhouses

accommodating extended families of 50 or more. While the typical house

is home to fewer family members these days, the Palaung continue their tradition in which parents host their married sons and their daughters-in-law.

Every Palaung village has a headman, whose duties involve making decisions for the village and ruling in disputes.

The visitor might be surprised by how well these guest huts are built. The Palaung are highly skilled in

construction. Their own houses are also wooden huts, which are raised high off the ground on stilts. These

days their houses are typically much smaller than in the past. Traditionally their houses have been longhouses

accommodating extended families of 50 or more. While the typical house

is home to fewer family members these days, the Palaung continue their tradition in which parents host their married sons and their daughters-in-law.

Every Palaung village has a headman, whose duties involve making decisions for the village and ruling in disputes.

The headman usually comes from the largest family in the village.

The headman usually comes from the largest family in the village.

In the village shown above and left, Palaung men are building a new house for a husband and wife who are expecting their first baby. Village men of all ages play some role in the construction, which symbolizes the wishes and blessing of the whole community. Since the Palaung still use working elephants, the mahoot (elephant trainer) also employs the village elephant to fell and transport timber for the construction of the house.

Photography copyright © 1999 - 2026, Ray Waddington. All rights reserved. Text copyright © 1999 - 2026, The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R. (2003), The Indigenous Palaung People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved January 28, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Palaung>

Web Links Nat worship documentary Burma Partnership Books Howard, M. C. and Wattanapun, W., (2001) The Palaung in Northern Thailand. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. Diran, R. K., (1997) The Vanishing Tribes of Burma. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. Naing, U. M., (2000) National Ethnic Groups of Myanmar. (trans. H. Thant) Yangon: Swiftwinds Books. Milne, L., (1924) Home of an Eastern Clan: A Study of the Palaungs of the Shan States. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.