The Indigenous Kaqchikel People

Ethnonyms: Cachiquel, Cakchiquel, Cakchiquiel, Caqchikel, Kakchiquel, Kaqchiquel Countries inhabited: Guatemala, Mexico Language family: Mayan Language branch: Quichean

The Kaqchikel are an indigenous Maya people who live mostly in the Highlands of southern Guatemala around Lake Atitlán. A very small number of them also live in Mexico. Like their Tz'utujil cousins, they emerged as a recognizable ethnolinguistic group during the late Post-Classic period of the Maya Empire — about four hundred years before the first Spanish colonists arrived in the New World.

They are the second-most populous Maya people in Guatemala, after the Kiche people. They represent 8.4% of the population there.

Much of what is known about the Kaqchikel from pre-colonial times comes from the Sixteenth Century manuscript, The Annals of the Cakchiquels. Written mostly by Francisco Hernández Arana Xajilá, it is a treatise covering ancient Kaqchikel history, knowledge, customs and culture etc. It was originally written in the Kaqchikel language (but in the Latin script because literacy in the Mayan script had been lost by the time).

Although it would have been informed by the Kaqchikel people themselves, it is written with a colonial mindset. It was translated into English in 1885. A link to that translation is given in the Citation and References section at the end of this essay.

When the Kaqchikel were acting as informants for the Annals, a scene like the one photographed above would have been very common. Of course, the photograph was taken hundreds of years later. It is indicative of how little has changed during that time for the Kaqchikel Maya. They are still largely subsistence farmers and fishermen, although wage labor now also forms a large part of the income for many families.

One thing that has changed is religion. Before the Spaniards arrived, Kaqchikel religion was comprehensive and polytheistic. It had its own idiosyncharies but it was similar at its core to other Maya religious practices. Chief among their deities were the maker, the fashioner, the begetter of sons, the bearer of children and the man of the woods. These and other gods influenced almost all aspects of daily Kaqchikel life.

The Spaniards rejected all Maya religions outright and considered it imperative that all Maya convert to Christianity. (The Catholic Church was extremely powerful in Europe at the time.) Kaqchikel religion survived only because it went underground and was practiced away from Spanish eyes. To this day, what appears to be orthodox Catholicism from afar is still peppered with remnants of their original religion.

Another recent change for the Kaqchikel is the amount of their contact with outsiders. Since the end of the civil war, Guatemala has become a popular tourism destination. Lake Atitlán is one of its favored destinations. The Kaqchikel live primarily in the small towns and villages that surround the lake. They have been quick to capitalize on new commercial opportunities.

They sell souvenirs, trinkets and traditional, hand-made clothes and handicrafts to the tourists. Often, as the photo above shows, young Kaqchikel girls are involved in this trade to supplement their family's income.

Selling direct to tourists is economically feasible in the larger towns of Sololá, Panajachel and Santiago Atitlán.

San Marcos La Laguna, on the western shore of the lake, is a very small Kaqchikel community by comparison. There, yoga, massage and other spiritually-based practices have become a cottage industry. That's not surprising since the whole village has a laid-back vibe about it.

Although the smaller lakeside Maya communities can now be reached by road, the residents themselves still rely on transportation by boat. One of the lesser-served (and, therefore, least visited) Kaqchikel communities is San Lucas.

It is the most isolated of the lakeside Kaqchikel communities, but it is still an interesting place to visit to witness modern Kaqchikel life and culture. Sitting in the shadows of Volcán Toliman (3,158m) and Volcán Atitlán (3,535m), San Lucas is home to the most traditional of all Kaqchikel communities.

Another little-visited Kaqchikel village is Santa Cruz La Laguna. It rests on a hillside but with easy access. Once tiny and tranquil, it has benefitted from the recent boom in tourism and it now offers many activities to its visitors. The cultural highlights of Santa Cruz are visiting the market and learning how to make traditional Kaqchikel beaded bracelets. Or, like I did, just walking through the village and meeting Kaqchikel people first-hand.

Just like all of the world's remaining indigenous peoples, the Kaqchikel are struggling to preserve their lifestyle and their culture. Perhaps they will lose their struggle one day. For now, though, they have a message for us.

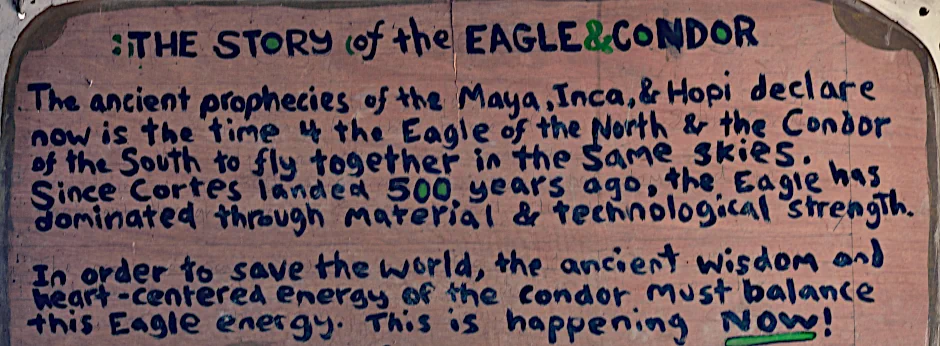

Hanging in a restaurant in a Kaqchikel restaurant where I ate was this sign. It reminds me of the struggle that the "Global South" is now facing from the effects of climate change to which those peoples hardly contributed. It also reminds me that if we are to help them in that struggle, indigenous knowledge will be a key factor.

Photography copyright © 1999 - 2026, Ray Waddington. All rights reserved. Text copyright © 1999 - 2026, The Peoples of the World Foundation. All rights reserved.

Waddington, R., (2023) The Indigenous Kaqchikel People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved February 11, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Kaqchikel>

Web Links Cakchiquel Language and the Kaqchikel Mayan Tribe The Annals of the Cakchiquels Books Brintnall, D.E., (1979) Revolt Against the Dead: The Modernization of a Mayan Community in the Highlands of Guatemala. New York: Gordon and Breach. Carey, D. and Burns, A.F., (2001) Our Elders Teach Us: Maya-Kaqchikel Historical Perspectives. Tuscaloosa: University Alabama Press. Garzon, S., McKenna Brown, R., Becker Richards, J. and Wuqu' Ajpub' (Arnulfo Simón), (1998) The Life of Our Language: Kaqchikel Maya Maintenance, Shift, and Revitalization. Austin: Univesity of Texas Press.