The Indigenous Baiga People

Ethnonyms: Bhuiyan, Bhuiyar, Bhumia, Bhumiaraja, Bhumij, Bhumija, Bhumijan Countries inhabited: India Language family: Indo-European Language branch: Eastern Hindi, Chhattisgarhi

The text and photographs on this page are copyright by Manish Gangwar and Pradeep Bose. Manish Gangwar is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Sociology at Barkatulla University, Bhopal, India. Pradeep Bose is the Director of the Aaspur Rural Development Project, District of Dungarpur, PKP, Raj., India.

The Baiga have been the forest-dwelling aboriginals from central India who claim to be harbingers of the human race and history in India, as it emanated from the conjugation of the Nanga (nude) Baiga as the Indian Adam and the Nangi (nude) Baigin (female Baiga), as the Indian Eve, who were the rightful progenitors of Indians. Baigas always believed that they were the chosen few who were hand-crafted by the God Himself and hence were the kings and rulers of the whole earth. They called God the Bhagwan or Bada Dev (big deity). They may have lived in Central India at least for 20,000 years. They practiced Bewar, a shifting, slash and burn method of growing crops. And hence the non-Baigas called them Bewadias, the practitioners of Bewar. It seems over the years, by the medieval period, Bewadia got its name distorted and was called by its derogatory name of Baigadia — those people who destroy land and forest by burning. By latter medieval times Baigadia shed the last three letters and became Baiga — by which name this community is still addressed and identified [1].

The Baiga have been the forest-dwelling aboriginals from central India who claim to be harbingers of the human race and history in India, as it emanated from the conjugation of the Nanga (nude) Baiga as the Indian Adam and the Nangi (nude) Baigin (female Baiga), as the Indian Eve, who were the rightful progenitors of Indians. Baigas always believed that they were the chosen few who were hand-crafted by the God Himself and hence were the kings and rulers of the whole earth. They called God the Bhagwan or Bada Dev (big deity). They may have lived in Central India at least for 20,000 years. They practiced Bewar, a shifting, slash and burn method of growing crops. And hence the non-Baigas called them Bewadias, the practitioners of Bewar. It seems over the years, by the medieval period, Bewadia got its name distorted and was called by its derogatory name of Baigadia — those people who destroy land and forest by burning. By latter medieval times Baigadia shed the last three letters and became Baiga — by which name this community is still addressed and identified [1].

Seven sub-castes of the Baigas are: Narotias, Binjhwars, Barotias, Nahars, Rai Bhainas, Kadh Bhainas and Kath Bhainas. However the authors found that Narotias, Barotias and Bhainas account for 80% of all the Baigas from Madhya Pradesh (MP) and Chhattisgarh states. In a small village, outside Baiga-Chak, authors found a few households of Dudh Bhainas and Kurka Bhainas also. Besides, there are at least 90 surnames that they use. Dhurve, Maravi, Rathudiya, Kohadiya, Kushram, Nadia, Nigunia and Nagvasia are their eight most common surnames.

There are three versions of the origin of the Baiga tribal community. One school of thought suggests that they actually emerged from the ancient stock of the Santal tribe. The second says that they emerged independently, but their ancestors had been the close kin of the Gonds.

The third does not accept Baigas' proximity either to the Santals or the Gonds, but calls them an independent tribe (Triloki Nath Madan) that emerged from the jungles of present day Rewa district of MP state in ancient times. Table 1 examines some of the comparative basic bodily data of the Gonds, the Baigas and the Santals.

| Tribal Name | Mean Adult Male Weight (kg) | Mean Adult Female Weight (kg) | Mean Adult Male Height (m) | Mean Adult Female Height (m) | Male Body Mass Index (kg/m²) | Female Body Mass Index (kg/m²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Santal | 50 | 44 | 1.65 | 1.49 | 19.5 | 18.5 |

| Baiga | 53 | 47 | 1.6 | 1.55 | 17.5 | 16.5 |

| Gonds | 54 | 48 | 1.63 | 1.55 | 22 | 19 |

Table 1. Comparative Body Parameters of Santals, Baigas and Gonds. (Sources: Ghosh and Malik, "Variation of Body Physique of the Santals", Anthropologist 34 (2010), New Delhi; Chakma, Meshram et al, Nutritional Status of the Baigas, Anthropologist 11 (1), 2009, New Delhi, Sharma; AN (Ed.), Contemporary Studies in Anthropometry, 2007, Sarup and Sons Publishers, New Delhi; Das and Bose, Anthropological Note Books 18 (2), 2012, Slovenia Anthropological Society; Chakraborti, Pal, Bharti 2008, Tribes and Tribals, Special Issue of Anthropologist 2: 95-101, New Delhi, (2008); Gautam and Adak Proceedings of National Symposium on Tribal Health, Tripathy and Mishra, 2011; Nutritional Status of Tribal Women (Both rural and Urban) In Orissa, The Socioscan, Vol. 3 (1 & 2) 30-42, Ranchi, India.

The authors found that the Baigas were generally smaller but were more compact looking than the Gonds and Santals. The aforesaid data suggest that in terms of body mass index the Baigas were the most diminutive of the three tribes. However, the Baiga women had greater height and weight than those of the Santals. Gonds, on the other hand demonstrated greater physical traits than the other two tribes, except that their males were an inch smaller than those of the Santals.

Gonds are the most numerous indigenous tribe of India, followed by the Santals and the Bhils [2]. Baigas have traditionally lived in Gond-abundant areas of Central and Western India.

Gonds are the most numerous indigenous tribe of India, followed by the Santals and the Bhils [2]. Baigas have traditionally lived in Gond-abundant areas of Central and Western India.

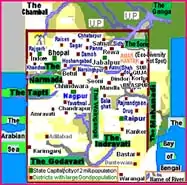

However since the 1950s the geographical spread of the Baigas has reduced to about one third of their total initial spread. Now they have three distinct geographical spreads. The largest grouping of the Baigas lives within 250 km of Jabalpur city in Mandla, Dindori, Balaghjat and Seoni districts. The second largest grouping of the Baigas lives in Bilaspur, Kabirdham and Surguja districts of Chhattisgarh. The smallest geographical grouping of the Baigas exists in Sidhi, Rewa, Satna, Shahdol, Mirzapur and Sonebhadra districts of Baghelkhand region, in both MP and Uttar Pradesh (UP).

However since the 1950s the geographical spread of the Baigas has reduced to about one third of their total initial spread. Now they have three distinct geographical spreads. The largest grouping of the Baigas lives within 250 km of Jabalpur city in Mandla, Dindori, Balaghjat and Seoni districts. The second largest grouping of the Baigas lives in Bilaspur, Kabirdham and Surguja districts of Chhattisgarh. The smallest geographical grouping of the Baigas exists in Sidhi, Rewa, Satna, Shahdol, Mirzapur and Sonebhadra districts of Baghelkhand region, in both MP and Uttar Pradesh (UP).

Sharma and Dwivedi [3] studied two large villages from Samnapur, Simardha and Tikariya; Gangwar and Bose [4] studied 20 Baiga villages in the Baiga Chak Belt of Dindori district.

The demographic details of these villages are given below.

Sharma and Dwivedi [3] studied two large villages from Samnapur, Simardha and Tikariya; Gangwar and Bose [4] studied 20 Baiga villages in the Baiga Chak Belt of Dindori district.

The demographic details of these villages are given below.

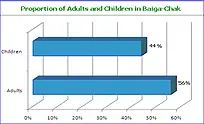

- Total Number of Households and Population studied = 400 and 1870.

- Households and Population studied by Sharma and Dwivedi = 100 and 494.

- Households and Population studied by Gangwar and Bose = 300 and 1376.

- Average Family Size = 4.68.

- Infant Mortality Rate = 323/1000.

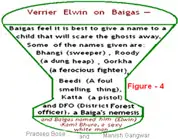

Baigas are fun-loving, even their names are fun, as stated by Dr. Verrier Elwin.

It seems Baiga families have recorded their history from ten to thirty thousand years ago in the rock shelters of Central Narmada Valley region of Hoshangabad and its adjoining districts. It seems that very dense forests in the Central Narmada Valley region consisting of ten modern districts of India's central province (MP), viz. Narsinghpur, Harda, Hoshangabad, Betul, Raisen, Sehore, Bhopal, Jabalpur and some parts of Sagar and Damoh were the original habitat of the Baigas. Baigas roamed around and lived in these forests freely. Besides, some of the Baigas, Korkus and Nahals lived in the forests of Tapti River Valley in the districts of Khandwa and Burhanpur. About 85% of the total geographical area in these districts had dense canopy forests. Baigas lived in these forests and carried out shifting, slash and burn cultivation for thousands of years without any influence or competition from other Indian residents or habitats. The Hindu Epics Ramayana and Mahabharta make many references to the uncivilized and naked, forest-dwelling, tree-burning, non-Devas or demons of Central India who practiced black magic and disturbed the Hindu sadhus, hermits and saints by breaking their meditation. These districts with few sparsely populated colonies, however, started to have increased human pressure by the year 1250 AD, when thousands of non-tribal caste Hindus migrated to these districts and started living there permanently. Only by the year 1530 AD, these districts, under the stewardship of the official emissaries, sent by Mughal Emperors, got densely colonized by the Moslems, Hindu peasants and trading classes from mainstream India. Subsequent to the rising population pressure in Central Narmada Valley region, it seems that the Baigas shifted to the freely available dense forests of Upper Narmada Valley and its highlands belonging to the five districts north of Jabalpur, viz. Seoni, Balaghat, Mandla, Shahdol and Bilaspur in the 1550s. Meanwhile, emergence of five small medieval Gond kingdoms in Central India attracted some of the Baigas to these Gond capitals to work as priests, indigenous physicians and sorcerers.

Baigas were virtually unknown aboriginals until the medieval Gond Kingdoms emerged. It was during the five Gond Kingdoms that many Baigas were appointed as royal priests, shamans and physicians. Baigas served their Gond kings very efficiently and effectively. Royal Baigas of Garha and Mandla kingdom, as well the Haihaya kingdom of Ratanpur became legendary figures. The co-existence of established Mughal and Gond kingdoms and the independent tribal community of the Baigas was quite amicable and did not threaten each other because the Baigas were left to live in their far-flung jungles, according to their own rules and customs. This co-existence carried on without much animosity till the entry of the British in India. In those days Central India was sparsely populated and was beyond the limits of centers of higher civilization. However, the British brought with them the idea of colonizing sparsely populated Central India and also the desire to exploit the great dense sal forests of Central India. The British did not adopt the policies of noninterference and enabling protection to the tribal populations to retain their land and their traditional life-style in Central India, as they did for those of India's North-East, Abhujhmar area and Brahamputra Valley. The British rulers believed that if the nomadic Baigas' Bewar was restricted to a small area, they could exploit the forest resources of Central India. Hence they created a small reservation of 100 square kilometers in 1890 and called it Baiga Chak. The British bureaucrats diverted thousands of roving Baiga households from Mandla and Dindori district to that reserved area. Gradually through the efforts of British administration and later after independence by the Indian administration the Baigas were dissuaded from undertaking Bewar. The Baigas, in Mandla, Dindori, Shahdol and Balaghat districts of MP, dumped shifting cultivation or Bewar for good and they became settled farmers by the year 1955. However, Bewar was still practiced in very small patches of Bilaspur and Kawardha districts of Chhattisgarh state.

The Baigas believe that their male ancestor the Nanga Baiga was a great magician. Besides, there have been four great Baiga magicians as their legends say. They were called Daugan, Nindhan, Danantar and Madhakwar. Nonetheless, the charms of Nanga Baiga were considered most potent and he was the premier Baiga wizard. Nanga Baiga's right shoulder was considered the source of white magic, and it contained red blood, whereas the left shoulder of Nanga Baiga was considered the source of black magic and bled black blood. The legend attests that the youngest son of the Nanga Baiga drank from his father's right shoulder and became a great white magician. The leading black magicians of ancient times were, as per the legend the 'kana' Gond and the 'langdi dhobin', because they drank from the left shoulder of the Nanga Baiga. Baigas generally have three grades of magicians: The top grade and most revered magician among the Baigas is called dewar. Dewar is considered a powerful magician who can cause rains, stop earthquakes and make the most ferocious tigers very docile. Baiga agricultural rites of Bidri are usually performed by the dewars. Gunia is the magician of the second order who has enough knowledge to deal with human and animal diseases. Jana Panda is the most common and belongs to the lowest grade of the magicians who knows all about good and bad omens and how to deal with these. He also knows how to interpret dreams. Some of the Baiga Jan Pandas and Gunias have been women. However, fewer than a dozen women historically have been accepted as the dewars by the Baiga community. About 90% of Baiga magicians are men.

Table 2 shows omens and dreams that are popular among the Baigas.

| Good Omens and Dreams | Bad Omens and Dreams |

|---|---|

| Cows, women, tigers, water, floods, vehicles approaching, corpses, pitchers full of water. | Vehicles leaving, ghosts, men, houses, pitchers empty of water, Karma song and dance. |

Table 2. Omens and Dreams of the Baigas.

About 70% of Baigas are still able to maintain their unique identity by observing the following identity codes.

- Women have tattoos but they do not put bindi.

- Women do not pierce their nose.

- Men keep long hair of about 20-25 centimeters and roll it to make a small knot on their mane.

- Men and women wear clothes above the knees/ankles.

- Women do not cover their heads.

- Songs and Dances of Dussehra, Karma, Dadaria, Phag, Bilma, Dadria, etc.

- Minor millets have still been the staple food of the Baigas.

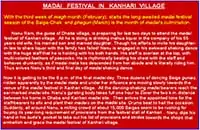

In the Baiga Chak belt there is a long celebration season. It begins with the harvesting that runs from mid January to the end of March. However the real festivities and non-stop drinking starts by late February. Kanhari Madai, Dhurkutta Madai,

Chada Madai and Baijag Madai are the four important madais of Baiga Chak belt. But the Madai of Mavai block, headquarter of Mandla district, is perhaps the largest Madai festival of the region. And the madai festival of Baijag is the best known madai of Baiga Chak. Text Box 3 shows the significance of this festival for the entire population of Baigas as thousands of them descend in Kanhari from as far as Jabalpur, Katni, Kawardha and Mandla districts.

In the Baiga Chak belt there is a long celebration season. It begins with the harvesting that runs from mid January to the end of March. However the real festivities and non-stop drinking starts by late February. Kanhari Madai, Dhurkutta Madai,

Chada Madai and Baijag Madai are the four important madais of Baiga Chak belt. But the Madai of Mavai block, headquarter of Mandla district, is perhaps the largest Madai festival of the region. And the madai festival of Baijag is the best known madai of Baiga Chak. Text Box 3 shows the significance of this festival for the entire population of Baigas as thousands of them descend in Kanhari from as far as Jabalpur, Katni, Kawardha and Mandla districts.

Dassehara is the occasion during which the Baigas hold their Bida observance — a sanitizing ceremony in which the men dispose all nefarious spirits that have been troubling them during the past year. There are four popular rituals that the Baigas undertake as festivals. Bida, Bidri, Cherta and Devli are such joyous festivals of the Baigas.

Cherta, Bidri, Bida and Devli are the ritual cornerstones sustaining the Baiga myth, which is related to Baiga belief system and faith. Three spirits of jeev, chhaya and bhut are basic components of a Baiga. Jeev is the spirit of the living that merges with the Bhagwan after man's death and at Bhagwan's wish re-appears in re-birth, Chhaya is the person's shadow or shade that may express itself as a frog and it hides behind Baiga's chullah or cooking stove. The third spirit is that of ghost or bhut that represents evil and failings, which must be buried deep or burnt to cinders in the burial or cremation ground. Every growing Baiga child not only learns about these Baiga myths and legends, she (he) participates by singing, dancing and joining the traditional festivities. Besides, a growing Baiga child learns many other skills, like the use of bow and arrows for hunting, learning tracking and setting traps, making bamboo baskets and learning other basic skills like catching fish. Cherta is the first festival of the year and is observed in January. It is a festival of Baiga children. Baiga children make various kinds of masks and don these to look like beggars and sadhus and start begging food grains, pulses and vegetables by moving from one house to the other within the village. After they beg enough they go near a perennial stream, cook and eat food. Some of the boys act as if they were crows and caw around. Children pelt and throw burning sticks at these acting crows and after the crows have disappeared children share the food among themselves.

The second key festival of the year is Bidri. It is the most important event of the Baigas that is observed at the outset of the agricultural season in the month June. This ceremony is conducted by a dewar under a Pakri tree (Ficus glomerata) or a sajha tree (Terminalia tomentosa). Through chanting mantra and sprinkling of liquor the dewar invokes Gods to bless the seeds. Bidri ceremony thus imbues the crop seeds with vigor and blesses them to grow potently amidst all opposing forces of nature. The third set of key rituals that the Baigas observe is called Devli or Nawa feast. Devli for Baigas involves making the very first harvested paddy crop to their most venerable ones, viz. Thakur Deo, Dharti Mata, Nanga Baiga and Nangi Baigin and then they eat it. While making symbolic offering to these four venerable ones, the Baigas also invoke upon the good spirits to ensure good harvests for the ensuing years, as well.

Bida is the fourth sacred observation by Baigas, whereby they rid themselves of all the hostile spirits in the month of October that might have lived with them during the last 12 months. The dewar or the village Godman, who is a revered Baiga, is invited as the master of ceremonies and makes traditional Bida chants and asks all evil spirits to get away from the households and villages of the Baigas. Sometimes offerings of chicken and coconut are made to rid the village of these evil spirits. Thakur Deo is the reigning God for the Bida ceremony. Hence Bida is the cleansing ceremony of the Baigas.

Baigas do not worship Gods as ubiquitous supreme lords. Rather each Baiga-God carries a positional power and designation that is inseparably linked to the God's assigned role. For example, Bada Dev/Bara Deo/Farsa Pen was assigned the Bhagwan or number one position among all Baiga Gods. Bada Dev (big deity) is called Budha Dev (old deity) and Mahadev (Lord Shiva) too. However, Mahadev of the Baigas is not the lord Shiva of the Hindus. Mahadev was always the lord of all free Baigas, animals, forests,

livestock and also of Bewar. This spirit of supreme or Bada Dev used to reside on the lofty branches and leaves of the forest tree species of saja (Terminalia tomentosa). But this God ceased His activities of promoting shifting cultivation among the Baiga community.

Baigas do not worship Gods as ubiquitous supreme lords. Rather each Baiga-God carries a positional power and designation that is inseparably linked to the God's assigned role. For example, Bada Dev/Bara Deo/Farsa Pen was assigned the Bhagwan or number one position among all Baiga Gods. Bada Dev (big deity) is called Budha Dev (old deity) and Mahadev (Lord Shiva) too. However, Mahadev of the Baigas is not the lord Shiva of the Hindus. Mahadev was always the lord of all free Baigas, animals, forests,

livestock and also of Bewar. This spirit of supreme or Bada Dev used to reside on the lofty branches and leaves of the forest tree species of saja (Terminalia tomentosa). But this God ceased His activities of promoting shifting cultivation among the Baiga community.

The second supreme God or Narayan Dev usurped the position of Bada Dev subsequent to the cessation of shifting cultivation by the Baigas. Narayan Dev is the carrier of the Godly spirit that looks after the welfare of all Baiga households and each member of the aboriginal Baiga community. Thakur Dev and Dharti Mata were together allocated the third supreme God's status. They are, as per the Baiga belief, spouses. Thakur Dev has been assigned the supreme role as the good spirit that lords over and looks after each and every Baiga habitat/village. Hence Thakur Dev is the supreme village or hamlet-level God. Dharti Mata (earth mother) has been identified as that female God who is utterly sensitive, whimsical, susceptible and amenable to other creatures' and Gods' malfeasance. She carries the good spirit of nature's primary resource: the soil, earth or sub-stratum, on which all living beings live and prosper. It is the primary duty of all Baigas to take utmost care of Dharti Mata, propitiate and worship her everyday. Besides, the God who was assigned the good spirit of causing precipitation, Bhimsen, the rain-God, was also placed at fairly exalted position of the Baiga-God-hierarchy. Ghansam Dev has also been assigned a singularly supreme position of carrying the good spirit of tempering the fiercest wild animals or tigers. Nanga Baiga (the naked male Baiga ancestor) and Nangi Baigin (the naked female Baiga ancestor) have been assigned the position after Ghansam Dev. In addition to these Gods there are 80-odd additional carriers of Baiga Gods' good spirits. But they hold lower positions than eight singularly supreme Baiga Gods, viz. Bada Dev, Narayan Dev, Thakur Dev, Dharti Mata, Bhimsen, Ghansam Dev, Nanga Baiga and Nangi Baigin.

The second supreme God or Narayan Dev usurped the position of Bada Dev subsequent to the cessation of shifting cultivation by the Baigas. Narayan Dev is the carrier of the Godly spirit that looks after the welfare of all Baiga households and each member of the aboriginal Baiga community. Thakur Dev and Dharti Mata were together allocated the third supreme God's status. They are, as per the Baiga belief, spouses. Thakur Dev has been assigned the supreme role as the good spirit that lords over and looks after each and every Baiga habitat/village. Hence Thakur Dev is the supreme village or hamlet-level God. Dharti Mata (earth mother) has been identified as that female God who is utterly sensitive, whimsical, susceptible and amenable to other creatures' and Gods' malfeasance. She carries the good spirit of nature's primary resource: the soil, earth or sub-stratum, on which all living beings live and prosper. It is the primary duty of all Baigas to take utmost care of Dharti Mata, propitiate and worship her everyday. Besides, the God who was assigned the good spirit of causing precipitation, Bhimsen, the rain-God, was also placed at fairly exalted position of the Baiga-God-hierarchy. Ghansam Dev has also been assigned a singularly supreme position of carrying the good spirit of tempering the fiercest wild animals or tigers. Nanga Baiga (the naked male Baiga ancestor) and Nangi Baigin (the naked female Baiga ancestor) have been assigned the position after Ghansam Dev. In addition to these Gods there are 80-odd additional carriers of Baiga Gods' good spirits. But they hold lower positions than eight singularly supreme Baiga Gods, viz. Bada Dev, Narayan Dev, Thakur Dev, Dharti Mata, Bhimsen, Ghansam Dev, Nanga Baiga and Nangi Baigin.

Baigas have been a great fun-loving people and all of them express themselves through participating in various dances and songs. Baigas innovate with the words as and when they sing. However, the contents of the songs do remain within the limits of each occasion. Many of these folk songs have been documented by Dr. Verrier Elwin in 1939 and Prof. S.C. Dube in 1947. We present below a description to two genres of Baiga songs and dances that we observed and heard during our multiple visits to the Baiga-Chak area.

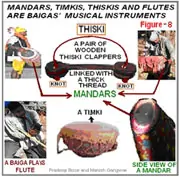

Baigas may be the inventors of the Karma dance that is now owned and performed almost by all the 40 million Central Indian aboriginals. Moreover, as Elwin says, Karma is the mother of all Baiga dances and all their dances are one or the other variant of the Karma. Songs are invented by the dancers or are standard practices made within the community for each mode and form of the karma dance. Baigas have dances separately for men, women and for both women and men together. For example, Reena, and Tapadi are danced by the girls. Sua or parrot dance is also an exclusive feminine dance. Saila is the exclusive male dance. Karma dances of two separate groups of men and women are the most common among the Baigas. Four to five Mandar/dhol drums dangled around the necks of prancing Baiga men make the principal and the most common percussion instruments to the Baiga's Karma dance, around which, generally, colorfully decked Baiga women dance in a circle.

The Dadaria: This is the oldest form of song and dance of the Baigas. Dadaria gives each Baiga a license to invent and sing any small song accompanied by some dancing steps. Dadaria songs are sung by both men and women. These are the trademark summary poetic expressions of every Baiga. These are contextual, situational and temporal earthy deductions derived from Baigas' life experience. Dadaria songs are generally couplets, quatrains, or sestets. These are metaphorical songs that contain similes, analogies and oxymora. In many instances Dadaria is sung either as expression of love by the Baiga-lover to his beloved, or a complaint of a Baiga wife to her husband, a didactic sermonizing parable, or it invokes the Forest-Gods. Most of the Dadarias start at dawn when Baigas leave their home and end with their return at dusk. Similarly, the first Dadaria is of birth and the last Dadariya is of death. Baigas sing these songs while gathering forest produce, collecting head-loads of firewood, wooing girlfriends and sometimes while even grazing animals. A Dadaria folk song may be sung as a lyrical rhapsody, having distinct meters and rhymes and others are mere soliloquies or statements of lust and love in free verse. In fact, Dadaria dance is based on the Dadaria song. All other folk songs of the Baigas occur as accoutrements to the folk dances. However, some of the amorous Dadarias may be profane or have graphic solicitation of love. A sample of some popular Dadaria songs is illustrated below:

"A lamp burns if its wick is oiled, Heart of a youth craves, even if he is asleep!"

"As you said that you wanted mangoes, I got the sweetest and largest of them all you said that you would come and eat these, I waited, days and nights, but you never came!"

"The new born farts and becomes a toddler He holds the stick and grows Boy rotates it in hands and grows Dangles and dangles, but of no avail How can one live without a beloved?"

"She stands mid stream, bathed in sesame oil her shadow shines, as the river cleans her rippling beauty and I pine tonight must be our rendezvous!"

"Lost in memories of the beloved, he draws water from the well he empties and drains the urn and swishes, as it wastes away; Here goes the lover, flowing down the hill And cries the beloved from the top, will I ever see him again?"

The Karma: This is the most important dance and song of the Baigas. Various forms of Karma songs and dances are popular with the central Indian tribes, including the Baigas. The advent of the most common Karma festival observed by the Baigas starts before the onset of the summer harvest by planting a branch of Nauclea parvifolia or cardiofolia (Karma tree) in the dancing arena and the community members dance around it. Karma songs are longer than Dadarias and are sung while dancing. Karmas are rhymes and are very pleasant to the ear. Because Karma songs comprise both men and women, sometimes they sing as duets, or as singing dialogues between men and women seeking answers to riddles. Moreover many Karma songs help the new generation learn from the sayings of the ancestors. Hence many songs convey teachings. Besides Karmas are rendered by the Baigas during various occasions like: greeting revered guests, singing competition between two neighboring Baiga villages, before an impending disaster and after experiencing it, seeking rains and hundreds of other occasions. A popular Karma song of the Baiga women is given below:

"I can't go to sleep, I can't go to sleep. Evening turns to dusk, then to night, Baigas go to sleep and some snore loud. Drums beat and Karma songs pierce through my sleep, I am wide awake I am wide awake, I can't go to sleep, I can't go to sleep. I nudge my spouse, 'rise and accompany me to the karma dance.' The fool scolds me and goes back to sleep, but I can't go to sleep. Lost in the beauty of Karma beats, I rise from the bed, take the pitcher. And whisper in his ear, 'I will be back with the pitcher full of water.' Crying all the way to the well, I fill the pitcher and come back slowly. But I find him asleep again and I cry, 'I can't go to sleep, I can't go to sleep.'"

"As dawn breaks, I place an urn on stove and heat it. Handing over a glass of warm water to him, I wake him. He smiles, as he washes his face and rinses his mouth My spouse thinks, 'She is happy. She must have gone out, sang and danced, as I was asleep.' He promises to take me to the dance, if beats and songs of Karma woke us up again." [It goes with taihu, taihu, taihu beat.]

Meanwhile, a popular Karma song of a male Baiga spouse is given below:

"Oh no, don't listen to your heart! Please, dare not push off, on your own I know your heart would waver and lead you against your own will. If such a thing ever happens ask me, my dear. I shall not hesitate and accompany you. Wherever your heart leads you to, just take me along. As I accompany you, I'll find ways to stem your embarrassment and pain. As I prove myself, your worthy spouse, you would be proud of me! Oh no, don't listen to your fickle heart, don't move furtively, not without me, ever! If you chose to take the northerly direction, you may find it full of deadly snakes. When you walk through alone, a tiger may appear and surprise you. And if you took a westerly road, after crossing miles and miles of barren land. You will come across rivers, in deluge, big enough to take in all of you, in a stride huge! I know, when you came back from such reckless wanderings, a lioness coming back to her lion. And his lonely den, you will know your poor hubby. What it means to be his spouse!"

Phag songs and dances do not have any tribal identity but are universally popular with the communities of the Chhattisgarh state. It has reference to the Holi Hindu festival of colors which starts in the third week of February and prevails till the end of March. It is the celebratory song that cheers the rural communities who live in south MP and Chhattisgarh. This dance heralds the bountiful harvests that are destined to come as the ensuing winter crops are harvested. Baigas have adopted Phag songs and dances as their own.

Phag songs and dances do not have any tribal identity but are universally popular with the communities of the Chhattisgarh state. It has reference to the Holi Hindu festival of colors which starts in the third week of February and prevails till the end of March. It is the celebratory song that cheers the rural communities who live in south MP and Chhattisgarh. This dance heralds the bountiful harvests that are destined to come as the ensuing winter crops are harvested. Baigas have adopted Phag songs and dances as their own.

There are five other Baiga folk dances that are popular with the community. These are: Shaila, Jharpat, Bilma, Rina and Sarhul. Shaila dance in a way is the heritage dance of the Baigas, whereby they depicted how their ancestors fought against the enemies of the tribe when they were attacked in the ancient times. The dance is performed in October. Five variants of Shaila have survived, of which Shaila dance of hunters or Shikari-Shaila still has dancing steps of chivalry, attack and chase. As the relic of old fighting form of the dance all variants of Shaila are still performed with sticks. The dancers, generally the men, sometimes a mixed group of men and women move in a circle and fight each other with sticks. However over the years the martial burlesque that depicted Baigas as warriors and fighting heroes, showing sword-like movements with the long sticks, have been replaced with small symbolic sticks and fighting moves have been replaced with sham efforts of the dancers who hit each other's stick, jump over each other and dance in circles. One may sometimes hear Baigas' singing as they dance Shaila steps, which end with 'tore nanare nana' like words, indicating that the Baiga youth are getting engaged in rowdy, obscene or pornographic version of the dance. These days another variant of Shaila dance, Dassera, is also practiced by the Baigas, which is necessarily a dance that declares the ripening of the summer crops with dancing steps and beats. Jharpat dance is a variant of the Karma dance. Eight to ten men stand in a horizontal row holding each other's hands and as many women stand opposing the men, also in a row, and hold hands with each other. Four to five male mandar or drum players stand between these two rows of men and women. It is in fact a dance of the young Baiga men and women, who sing taunting songs while dancing, which is necessarily foot tapping, going left-right or forwards-backwards, while bending forward. Even some riddles are asked by the women of the men and vice versa during this dance.

Historically Bilma had been a marriage dance of a bride's separation from her family. It signified the pain of the bride's family after their daughter went away to live with her in-laws. The mandar beats of Bilma are very loud and fast. Other instruments used are flute and timki. These days the motif of Bilma has changed. It has rather become a dance and song of summer harvest celebration whereby one group of dancers from a village goes dancing to the next village and people from the latter village also join the dancers of the first group. Rina is the dance of Baiga women. About eight to twelve women participate together wearing their traditional dancing dresses. They take small prancing steps, first backward and then forward, with the beat of the mandar and other percussion instruments.

Sua or parrot dance of Baiga women is the parrot burlesque performed by women. Women generally watch carefully the locomotive movements of the parrots' body parts along with the display of their wariness. It is elegance and beauty personified if a group of women have learned and practiced these moves for years. Sua is generally danced in early October or late September. Dance starts by women taking parrot-like careful steps, shaking, bending or jerking their heads as if they were parrots. Thiskis, the paired sonorous wooden clapping instruments, are the only instruments used in this dance. A central and better looking Baiga-woman among two dancing parallel lines of about five women each carries an earthen pot on her head with a wooden parrot, freshly sprouted paddy seeds and rice. This central woman keeps revolving like a top around her heels. As soon as the first row of women stops dancing the central parrot-carrying-woman shows her back to the first group of dancers and faces the second row of dances who start dancing as soon as the first row stops. The central dancer keeps circling with half clockwise and anti clockwise rotations, but always faces the dancing row of women.

There are seven sets of religious rituals observed by the Baiga community. These rituals are called pujas or worships. First four of these have been covered as festivals of Bida, Bidri, Cherta and Devli. Over and above these rituals, there are three additional rituals of the Baigas, viz. Motidhara, Ladoo kaj puja and Kathar puja. These are conducted once every three to five years. Ladoo-kaj-pooja is not liked much by the present day Baigas as they believe it to be very barbaric as one of its rituals involves placing a live pig in a pit and killing it slowly by pouring several pots of boiling water on it.

Notes

[1] There does not exist any documented proof of how Bewadias became Baigas. The authors arrived at this conclusion through a series of focus group discussion with senior Baiga citizens and non-Baigas.

[2] There are no recent population census data available for these three most populous tribes of India. However, per the estimates of the authors there are about 20 million Gonds, 17 million Santals (including Hos, Mundas, Korkus, Koles) and about 10 million Bhils.

[3] Sharma, AN, Dwivedi, Pankaj: Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Baigas in Samnapur Block of Dindori District, Anthropologist 8 (3), 2006.

[4] Gangwar, M., and Bose, P. (2012), "A Sociological Study of the Livelihoods of the Baigas in Baiga-Chak Belt of Dindori, India." The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved July 20, 2013, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/guestArticle.jsp?article=baigas>

Photography and text © 2013, Manish Gangwar and Pradeep Bose. All rights reserved.

Gangwar, M., and Bose, P. (2013), The Indigenous Baiga People. The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved March 7, 2026, from The Peoples of the World Foundation. <https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/text?people=Baiga>