A Sociological Study of the Livelihoods of the Baigas in the Baiga-Chak Belt of Dindori, India — Baigas

The text and photographs on this page are copyright by Manish Gangwar and Pradeep Bose. Manish Gangwar is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Sociology at Barkatulla University, Bhopal, India. Pradeep Bose is the Director of the Aaspur Rural Development Project, District of Dungarpur, PKP, Raj., India.

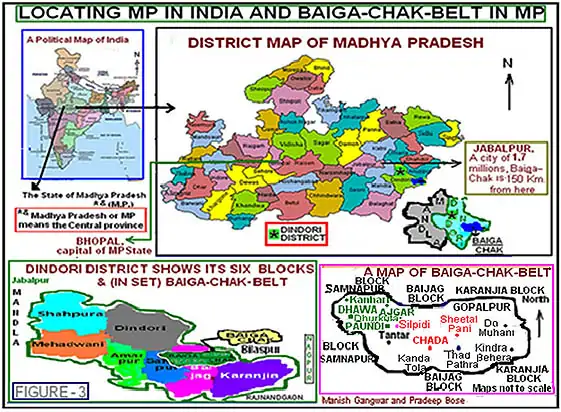

About 65 percent of the entire population of Baigas in India (some Baigas are in Bangadesh also) live in six districts of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. We estimate that there are about 350,000 Baigas living in India.

If we also include the Binjwars of Chhattisgarh and Odisha as a Baiga clan, and add their population, then the total number of Baigas in India is about 390,000.

There are four Baiga-major districts in MP — Mandla, Dindori, Balaghat and Shahdol (along with Umaria and Anuppur, two newly carved out districts from Shahdol). Two Baiga-major districts in Chhattisgarh are Kawardha and Bilaspur. Each of these six districts has at least 25,000 Baigas. We estimate that Rajnandgaon, Durg and Surguja districts of Chhattisgarh together have 12,000 Baiga residents. Moreover, about 5,000 Baigas live in each of three Baghelkhand districts of Sidhi, Singrauli and Rewa. A few thousand Baigas live in Mirzapur and Sonebhadra districts of UP, neighboring the well-known district of Varanasi or Benares.

About 65 percent of the entire population of Baigas in India (some Baigas are in Bangadesh also) live in six districts of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. We estimate that there are about 350,000 Baigas living in India.

If we also include the Binjwars of Chhattisgarh and Odisha as a Baiga clan, and add their population, then the total number of Baigas in India is about 390,000.

There are four Baiga-major districts in MP — Mandla, Dindori, Balaghat and Shahdol (along with Umaria and Anuppur, two newly carved out districts from Shahdol). Two Baiga-major districts in Chhattisgarh are Kawardha and Bilaspur. Each of these six districts has at least 25,000 Baigas. We estimate that Rajnandgaon, Durg and Surguja districts of Chhattisgarh together have 12,000 Baiga residents. Moreover, about 5,000 Baigas live in each of three Baghelkhand districts of Sidhi, Singrauli and Rewa. A few thousand Baigas live in Mirzapur and Sonebhadra districts of UP, neighboring the well-known district of Varanasi or Benares.

Through our visits to four districts of Baghelkhand region, i.e. Shahdol, Sidhi, Singrauli and Rewa, we have ascertained that many Baiga inhabitants there worked as halwahas, as do thousands of Kol tribals from the Munda stock. Halwaha is a euphemism used for bonded laborers. Halwahas are employed by the large landlords of Baghelkhand and in many instances they do not have their own homes and live in make-shift houses provided by the landlords.

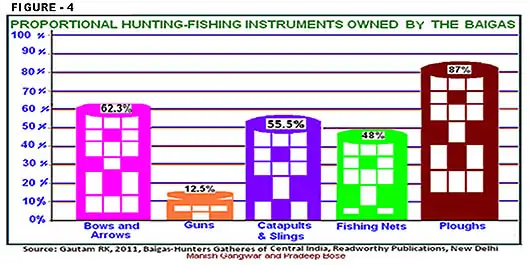

R. K. Gautam (see [6]) states that the Baigas in the twenty first century are not dependent upon hunting and food-gathering alone. However, Baigas of Baiga-Chak are still dependent significantly on hunting, fishing and forest produce gathering and they were engaged in primitive forms of agriculture. We found that only fourteen of 52 villages of the BCB had ample flora and fauna near the villages to make hunting and forest produce gathering significant.

Moreover, hunting of most of the animals that Baigas traditionally were engaged in have now been included under the list of protected wildlife, like chital, black buck, local deer or blue bull. However, they do hunt small animals and birds, like rabbits, wild boar, wild fowl and partridges etc. [6]. Gautam further adds that earlier the Baigas collected only food items, but now they collected some such forest produce too that they could sell in the market. He lists nine food items, viz. mushrooms, bamboo shoots, tuber roots, both flower and fruit of mahua, chironji or char, gums and resins, fruit of Bhilma (Semecarpus anacardium), trifala fruits, viz. aonla (Emblica officinalis), harra (Terminalia chebula) and baheda (Terminalia bellirica) and also jungle-honey.

Detailed documentation of sociological, anthropological and economic spheres of Baigas' lives has been depicted by legendry British scholar Dr. Verrier Elwin (1939, 1943). Besides the work of Russell and Hira Lal (1919), Philip McEldowney's (1980) Ph.D. thesis on Baigas and books by Gadgil and Guha (1993, 1995) have also made substantive contribution to building the corpus of knowledge related to the Baiga tribe.

Verrier Elwin (1939) in his book The Baiga made an intrinsically Indian ethnic expression about the livelihoods of the Baigas. He wrote that Baigas were like the bare holy cows of India who were timid, innocuous and did not have any foresight to plan for their livelihoods; for they were dependent on the there and then unlimited resources of the forests, wherever they lived. However since Elwin wrote his book, through the seven and a half decades of a complex acculturation process, the contemporary Baigas have changed significantly, not only into street-smart human beings but also as an indigenous tribal community that is very conscious and protective of its limited available portfolio of just four to five livelihoods.

McEldowney (1980) refers to a study conducted in 1888 by the district administration which investigated the earnings of a Baiga family in Balaghat district, who made bamboo baskets to earn money to buy food. The family consisted of a Baiga man, his wife and two small children. They made twelve baskets a week, selling each for two pounds of rice or millet. The earnings of 100 pounds of un-husked grain, or less than Rs. 1 per month got supplemented by the collection of forest roots and fruits. They saved about Rs. 1 each year for clothing.

Detailed documentation of sociological, anthropological and economic spheres of Baigas' lives has been depicted by legendry British scholar Dr. Verrier Elwin (1939, 1943). Besides the work of Russell and Hira Lal (1919), Philip McEldowney's (1980) Ph.D. thesis on Baigas and books by Gadgil and Guha (1993, 1995) have also made substantive contribution to building the corpus of knowledge related to the Baiga tribe.

Verrier Elwin (1939) in his book The Baiga made an intrinsically Indian ethnic expression about the livelihoods of the Baigas. He wrote that Baigas were like the bare holy cows of India who were timid, innocuous and did not have any foresight to plan for their livelihoods; for they were dependent on the there and then unlimited resources of the forests, wherever they lived. However since Elwin wrote his book, through the seven and a half decades of a complex acculturation process, the contemporary Baigas have changed significantly, not only into street-smart human beings but also as an indigenous tribal community that is very conscious and protective of its limited available portfolio of just four to five livelihoods.

McEldowney (1980) refers to a study conducted in 1888 by the district administration which investigated the earnings of a Baiga family in Balaghat district, who made bamboo baskets to earn money to buy food. The family consisted of a Baiga man, his wife and two small children. They made twelve baskets a week, selling each for two pounds of rice or millet. The earnings of 100 pounds of un-husked grain, or less than Rs. 1 per month got supplemented by the collection of forest roots and fruits. They saved about Rs. 1 each year for clothing.

Trading forest produce like mahua (Madhuca indica), fish, honey, musli (Chlorophytum borivilianum) and in recent years tendu (Diospyros Melanoxylon) leaves etc. for turmeric, common salt, wheat, condiments, cloth has been known to the Baigas for about 300 years now. Earlier they they used to drink from sulfi-wine palm (Caryota urens) trees. Later they picked up making bamboo baskets and brewing mahua-liquor to barter for market goods too. However, the tribal community of Baigas, who used to have open and ample access to their commons, i.e. forests, have since the days of Baiga-Chak formation, had to diversify their livelihoods for mere subsistence. The new generation of the Baigas now understands the limitations of private property and value of skilled labor in modern markets. However, they are still trying to internalize the concept of building surplus and saving money and these ideas have gradually been adopted by some Baiga households.

The British government started the census mechanism during the rule of Viceroy Rippon, in 1881. There were about 30,000 Baiga households and total population of about 1.36 lakhs, as per the second decadal census in 1891. Most of the Baigas in those times lived in about 30,000 sq. Km. of very dense forest, belonging to the modern nine districts of Mandla, Dindori, Balaghat, Shahdol, Sidhi, Singrauli, Kawardha, Surguja and Bilaspur. These Baiga families used to live in hordes of about twenty families in each location. Baigas did not settle in an area for good, rather they would inhabit a jungle area for about three to four years, as a transitory camp of about 100 persons from 20 families, conduct Bewar/slash and burn cultivation and then go to another location. There were about 1,500 such roving bunches/hordes of Baiga families who covered this entire forest area of 30,000 Sq. Km. Hence each Baiga household practically had one Sq. Km. of dense forest area to draw its sustenance. The Baigas had been living their own way as described above for about 20,000 years. But with the arrival of the British as the new rulers of Central India in 1860, Baigas were a hounded lot, tormented for practicing Bewar and in many cases they had to remain silent when the British rulers and their officials burnt Baigas' standing Bewar crops just to teach them a lesson.

Notes

[6] Gautam R. K., (2011) Baigas: The Hunter Gatherers of Central India. New Delhi: Readworthy Publications.

Photography and text © 2012, Manish Gangwar and Pradeep Bose. All rights reserved.

Gangwar, M., and Bose, P. (2012), "A Sociological Study of the Livelihoods of the Baigas in Baiga-Chak Belt of Dindori, India." The Peoples of the World Foundation. Retrieved

March 12, 2026,

from The Peoples of the World Foundation.

<https://www.peoplesoftheworld.org/hosted/baigas/>